Adiponectin and Clinical Blind Spots

Why the most abundant hormone you’ve never heard of might be the key to the South Asian metabolic puzzle.

On the Substack, we’ve spent the last few weeks building out a map of the South Asian metabolic phenotype with beta cells, ghrelin, mitochondrial efficiency, genotypes.

Today we add another layer: adiponectin.

You’ll need some chai for this as this will be the most in-depth piece we have done so far.

TL;DR

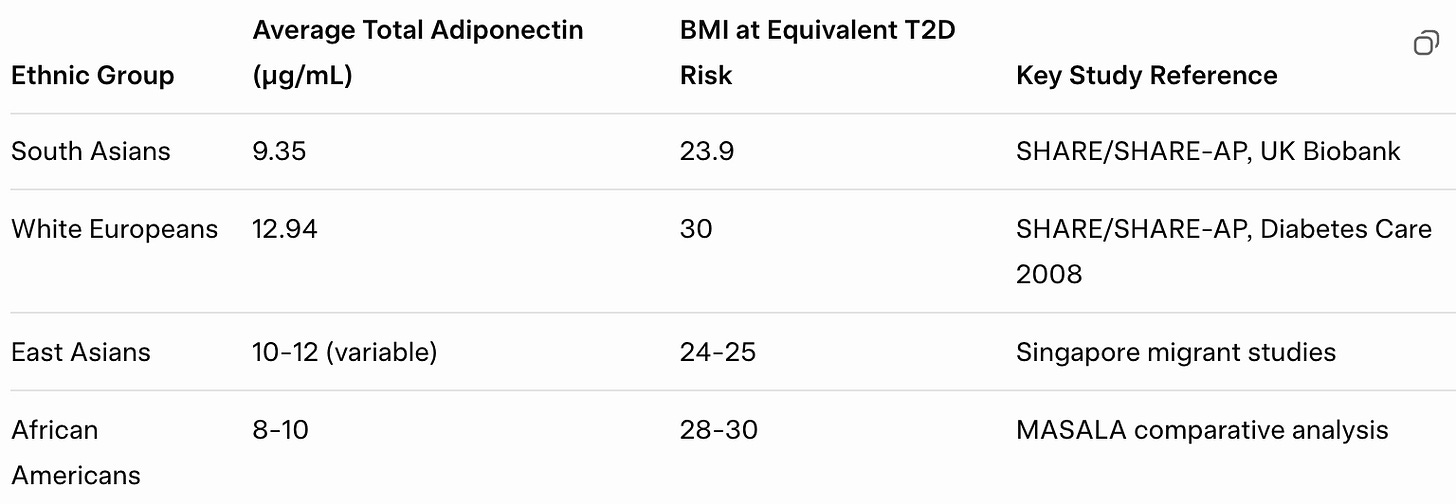

South Asians reach the same diabetes risk at BMI 23.9 that White Europeans reach at BMI 30; a six-point gap that standard charts completely miss. The question is why our bodies cross metabolic thresholds so much earlier.

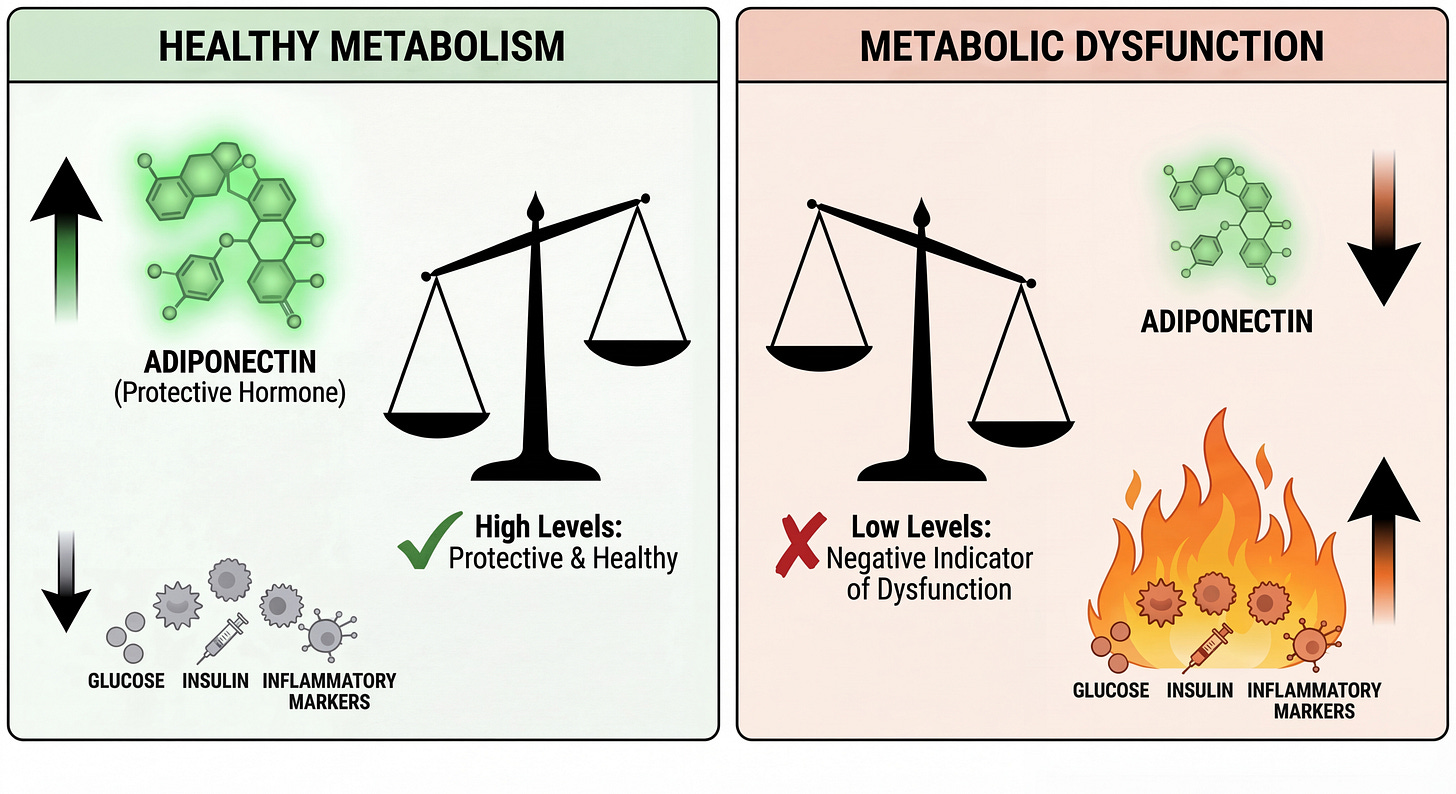

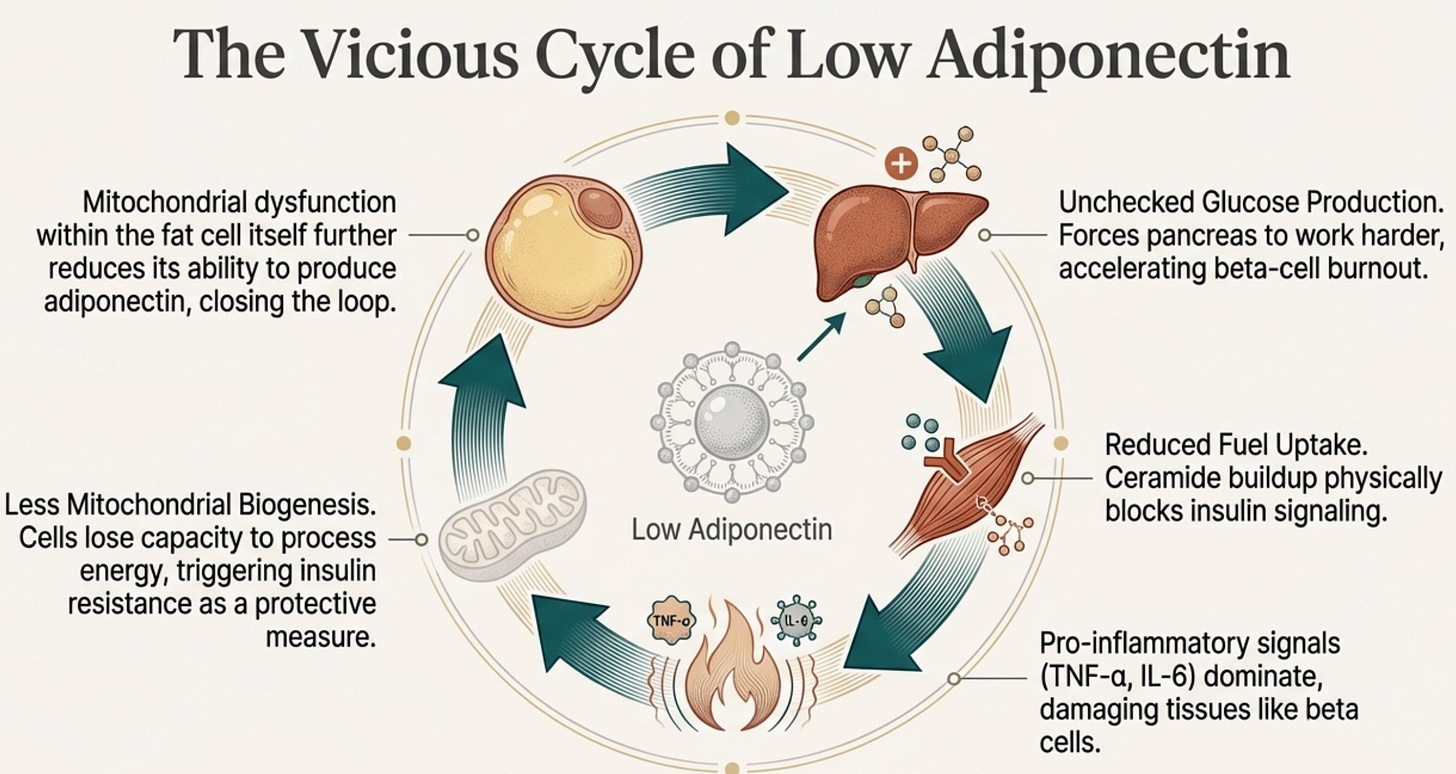

Adiponectin is a big part of this, the most abundant hormone you’ve never heard of, secreted by healthy fat cells to keep metabolism in sync. It tells your liver to stop dumping glucose, tells your muscles to accept fuel, activates AMPK (the master energy switch), and suppresses inflammation. When it falls, the orchestra descends into chaos.

South Asians have constitutively low adiponectin from birth, independent of obesity. MASALA study data shows our levels run 15-30% lower than White populations at matched BMI. This isn’t something we develop; it’s something we’re born with, written into ADIPOQ gene variants that affect both production and multimerization.

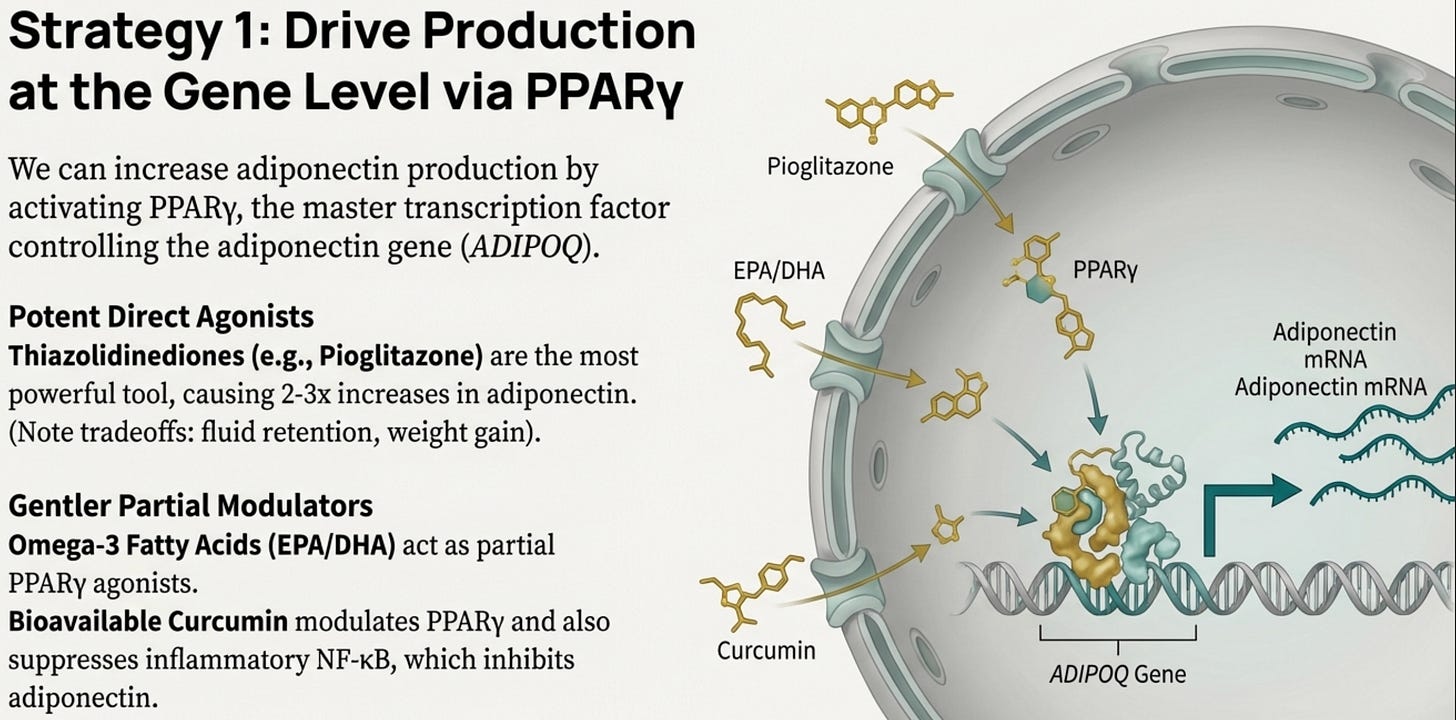

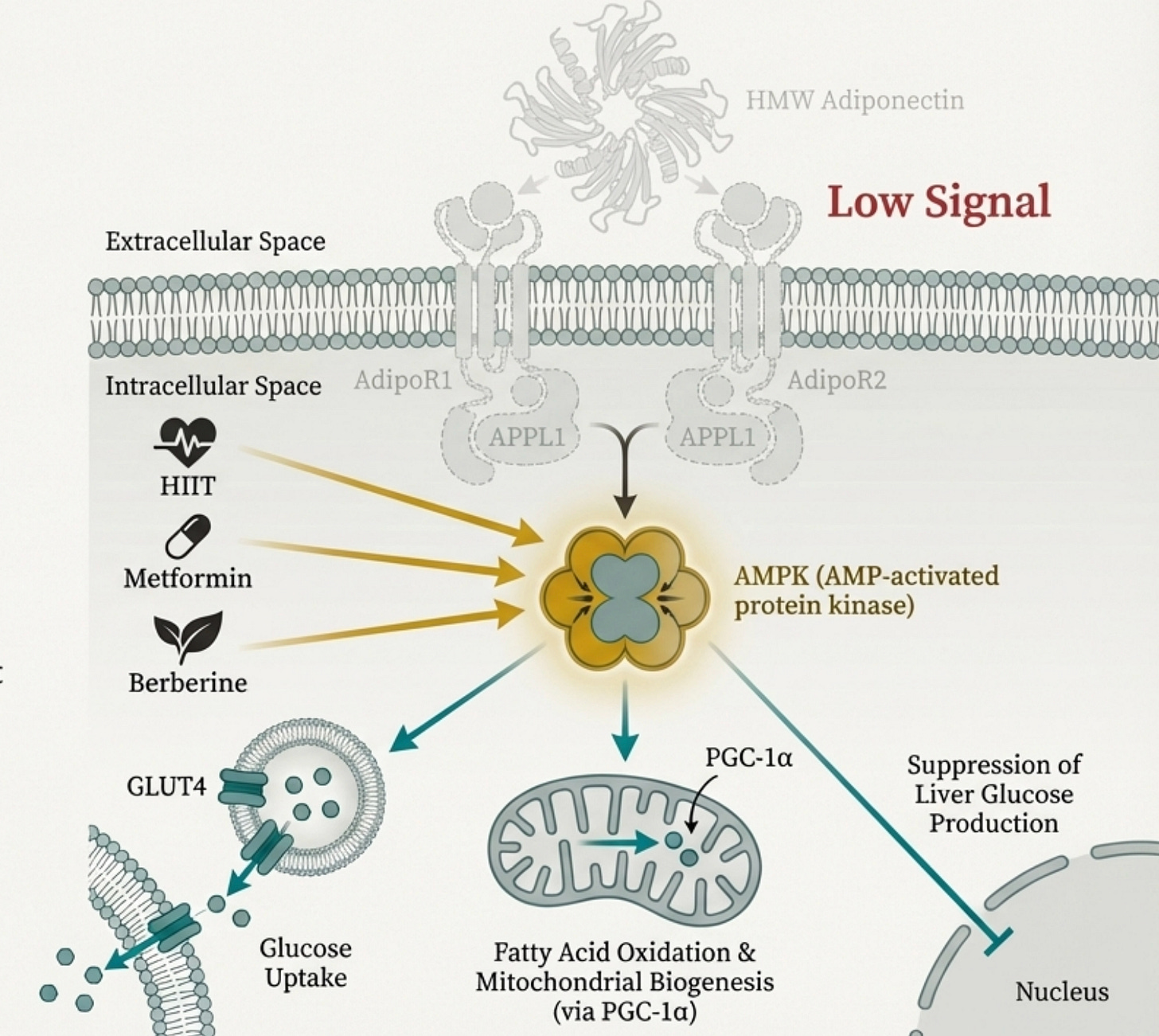

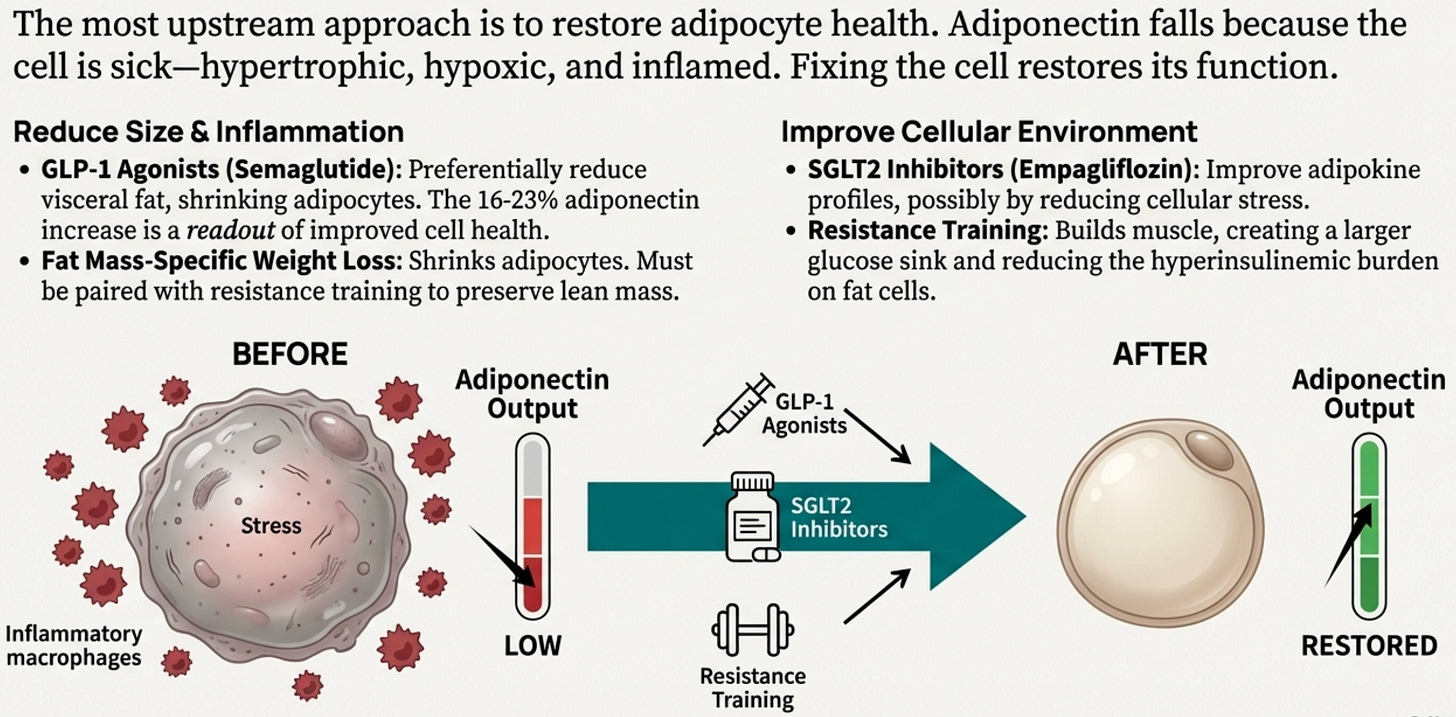

There’s no adiponectin pill (we discuss why), but there’s a three-part intervention framework: (1) activate PPARγ to drive transcription (omega-3s, curcumin, TZDs in refractory cases), (2) bypass the missing signal by activating AMPK directly (HIIT, berberine, metformin), and (3) rehabilitate the sick adipocyte itself (GLP-1 agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, resistance training, weight loss that preserves muscle).

The practical approach: recalibrate your thresholds (BMI ≥23, waist ≥90cm men / ≥80cm women), request the right tests (fasting insulin, apoB, consider adiponectin), target visceral fat not just weight, and advocate for yourself, the clinical guidelines were built on European cohorts and systematically underestimate your risk.

You know the story. Your uncle, the one who walked five miles a day, never touched alcohol, wore the same 32-inch waist he had at his wedding, had a heart attack at 54. Your mother’s fasting glucose crept past 100 despite her being “thin.” Your cousin, a competitive swimmer in college, developed Type 2 diabetes before his 40th birthday. The doctor said his BMI was “normal.”

In South Asian families, we’ve learned to expect this.

We joke darkly about the “desi tax,” the sense that our bodies operate by different rules, that the metabolic dice are loaded against us.

What we haven’t been told is why.

The answer, or at least a central piece of it, is a hormone called adiponectin. And if you’ve never heard of it, you’re not alone. Most physicians don’t measure it. Most medical schools barely mention it. But understanding adiponectin may be the single most important thing you can do to make sense of why South Asian bodies fail in the specific ways they do, and what we can actually do about it.

The Paradox in the Exam Room

Picture this scene, repeated thousands of times daily across clinics in London, Toronto, Houston, and Mumbai:

A mid 30s South Asian man sits on an exam table. His BMI is 24.5, squarely “normal” by the chart on the wall. His total cholesterol is 195. His doctor smiles, tells him everything looks great, and suggests he come back in a year.

What the chart doesn’t show: this man has the visceral fat distribution of someone 50 pounds heavier. His liver is quietly accumulating fat. His fasting insulin is elevated, his pancreas is already working overtime to maintain normal glucose. Inside his fat cells, a silent inflammatory cascade is suppressing the very hormone that could protect him.

Five years later, he’ll be diagnosed with diabetes. Seven years after that, he’ll have his first cardiac event. His doctor will be surprised. He shouldn’t be.

A landmark UK study of 1.47 million people quantified what South Asian families have observed for generations: we reach the same Type 2 Diabetes risk at BMI 23.9 that White Europeans reach at BMI 30. That’s not a rounding error. It’s a six-point gap, the difference between “you’re fine” and “you need intervention now.”

Using standard BMI cutoffs, approximately 36% of South Asians with undiagnosed diabetes are told they’re healthy.

The question is: what makes our bodies cross the threshold so much earlier?

The Hormone That Should Be Protecting You

For most of medical history, we thought of fat as storage. Passive. Inert. A depot that expands when you eat too much and shrinks when you don’t. End of story.

We were completely wrong.

When I was in training as a medical resident, a mentor once told me that that we probably only know 10-15% of what the adipocyte actually dose. That we would find it to be consequential in ways unimagined. That stuck with me and was an inspiration. Not only into adipocytes, but to constantly think that there is always something we may not know, and a big reason for this Substack.

So what is the adipocyte?

The adipocyte, or the fat cell, is an endocrine organ. It synthesizes and secretes dozens of bioactive molecules called adipokines that communicate with your liver, muscle, pancreas, brain, and blood vessels. Your fat tissue isn’t just sitting there. It’s talking to the rest of your body constantly.

Think of adipocytes as sending messages.

Some letters are distress signals: “Help! I’m stressed, I’m hypoxic, I’m inflamed, send backup!” These are the pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, TNF-α, and resistin. When your fat tissue is unhealthy, these letters dominate.

Other letters are status reports: “All systems normal. Metabolism running smoothly. Keep the gates open.”

Adiponectin is the most important of these protective letters.

It circulates at remarkably high concentrations 3 to 30 μg/mL, roughly 0.05% of your total serum protein. No other adipokine comes close to this abundance. Evolution invested heavily in adiponectin, which tells us its functions are fundamental to survival.

What Adiponectin Actually Does

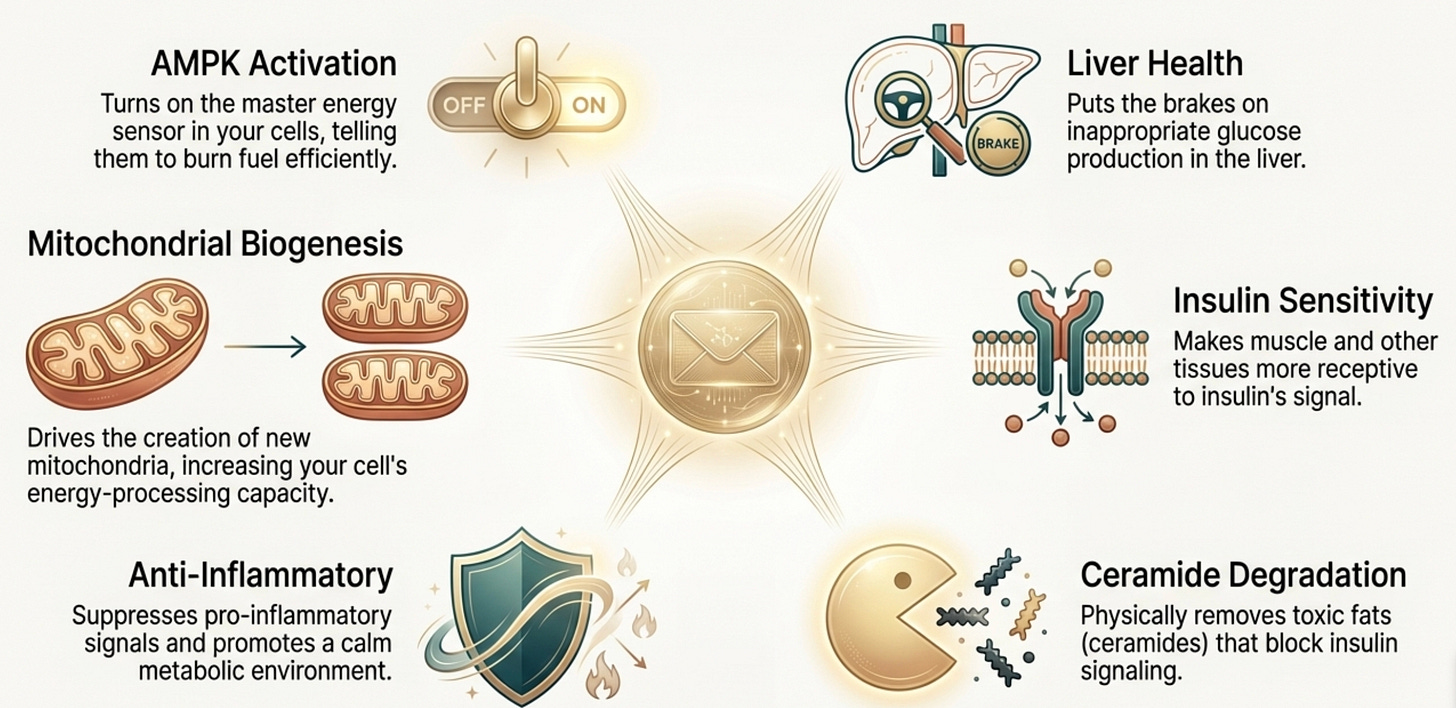

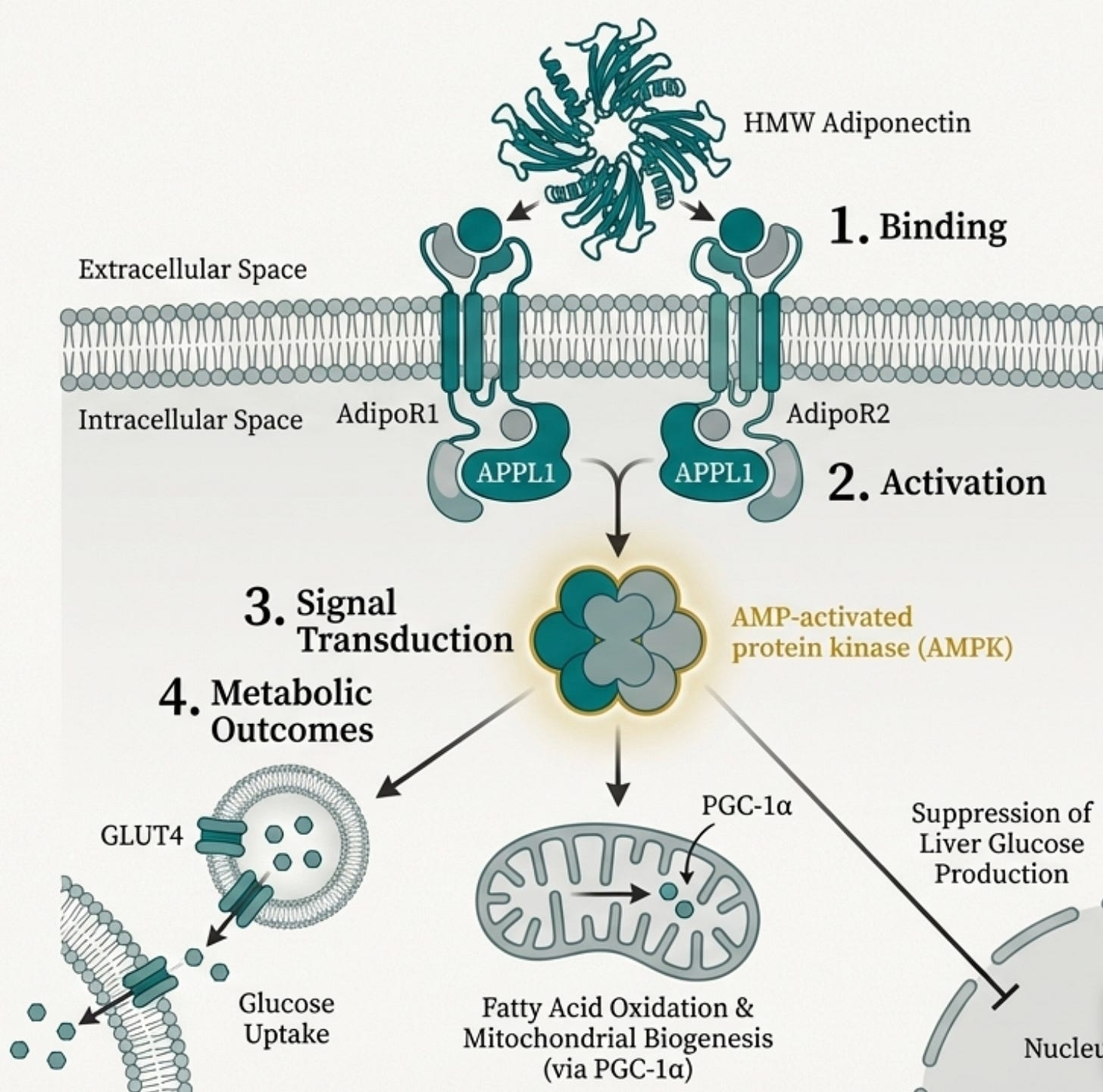

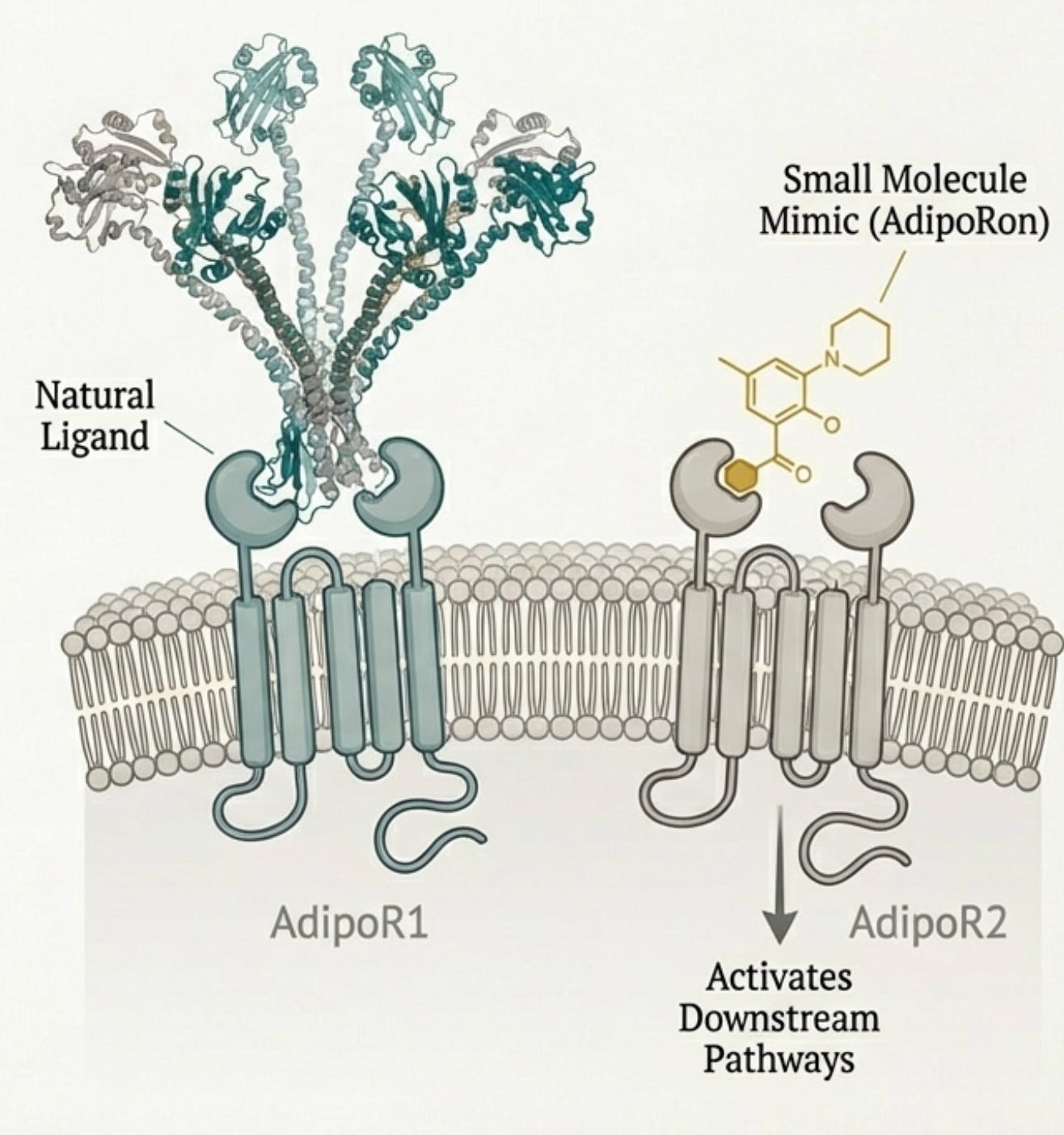

When adiponectin binds to its receptors (AdipoR1 in muscle and brain, AdipoR2 in liver), it triggers a cascade that touches almost every aspect of metabolic health.

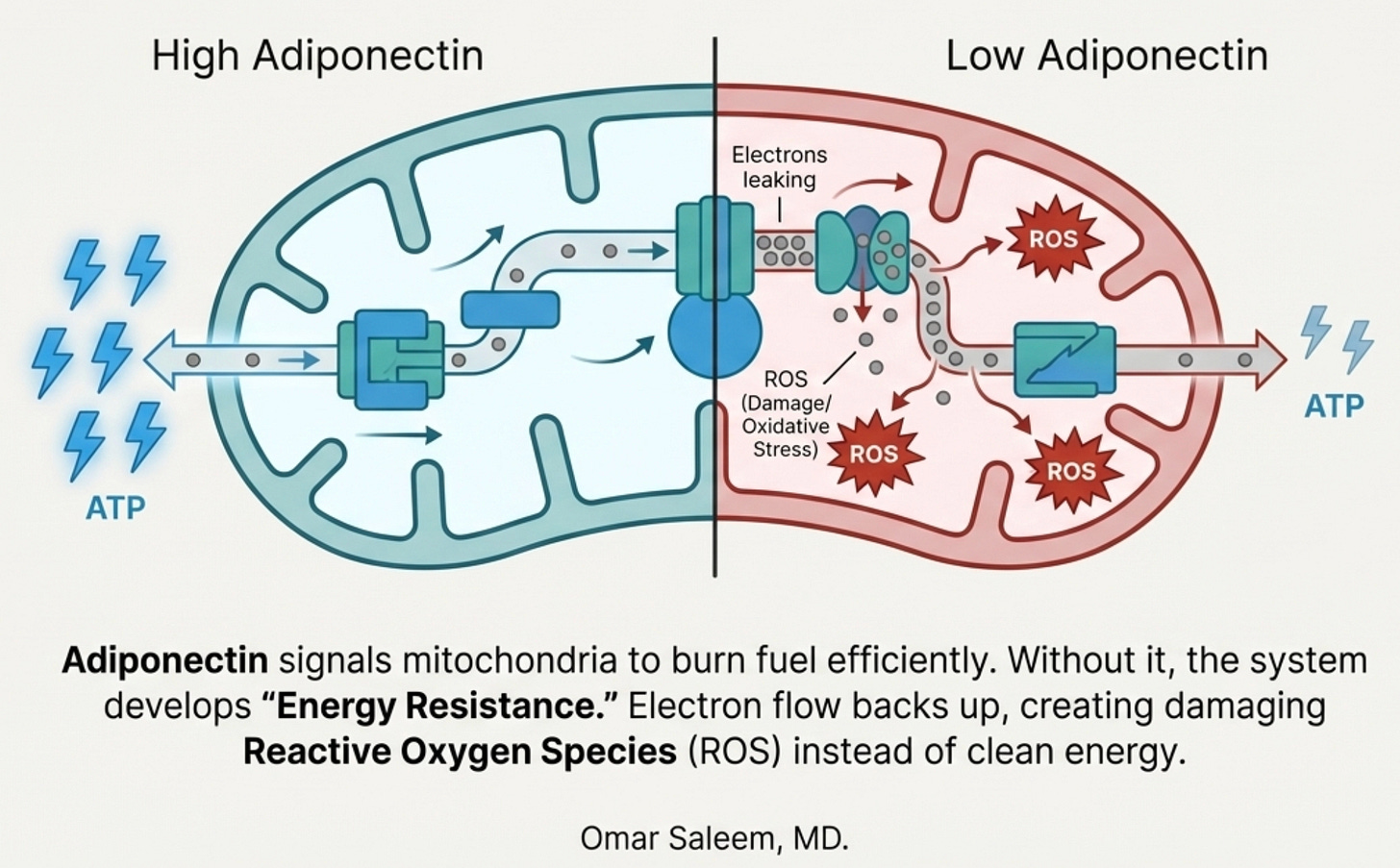

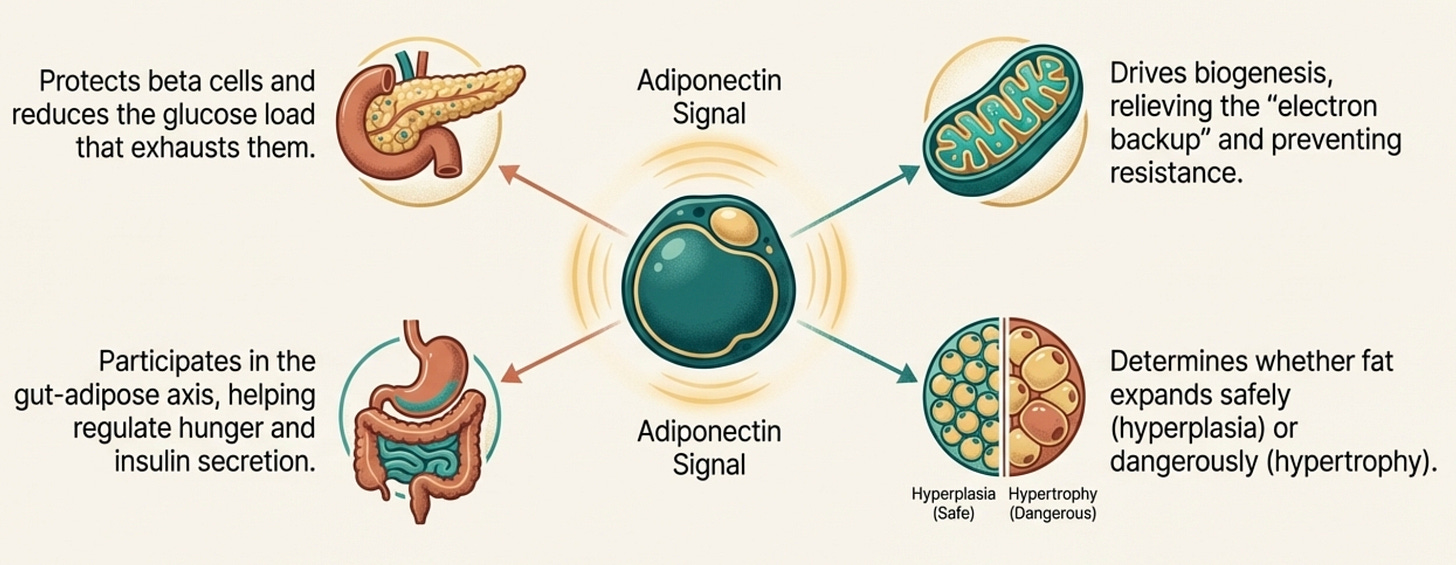

AMPK Activation: Adiponectin is one of the most potent physiological activators of AMPK, the master energy sensor. When AMPK switches on, your cells increase glucose uptake, ramp up fatty acid oxidation, and improve mitochondrial function. It’s the signal that says “burn fuel efficiently.” This, as we will learn further, it is of paramount importance in both metabolic function and mitochondrial functiona.

Hepatic Glucose Suppression: In the liver, adiponectin puts the brakes on gluconeogenesis. Less inappropriate glucose dumping into your bloodstream means less demand on insulin secretion to clean it up.

Insulin Sensitization: Through both AMPK-dependent and independent pathways, adiponectin makes your tissues more responsive to insulin. The doors to glucose entry stay open.

Ceramide Degradation: This one is underappreciated. Adiponectin receptors have intrinsic ceramidase activity, they directly break down ceramides, which are toxic sphingolipids that impair insulin signaling. Adiponectin doesn’t just improve insulin sensitivity through signaling; it physically removes one of the molecular species that causes resistance.

Anti-Inflammatory Effects: Adiponectin suppresses TNF-α and IL-6 while promoting anti-inflammatory cytokines. It keeps the immune system from attacking your own metabolic machinery.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis: Through the AMPK-PGC-1α axis, adiponectin drives the creation of new mitochondria. More mitochondria means more capacity to process energy without backing up.

When adiponectin is abundant, it acts like a skilled conductor keeping an orchestra in sync.

When adiponectin falls, the orchestra descends into chaos. Your liver ignores insulin’s signals. Your muscles become resistant. Inflammation rises. Fat accumulates in places it doesn’t belong; your liver, your pancreas, threaded through your muscle fibers. Your mitochondria, starved of the signal to burn efficiently, begin to sputter and produce reactive oxygen species instead of clean energy.

When adiponectin falls, all of this unravels.

The Isoform Problem

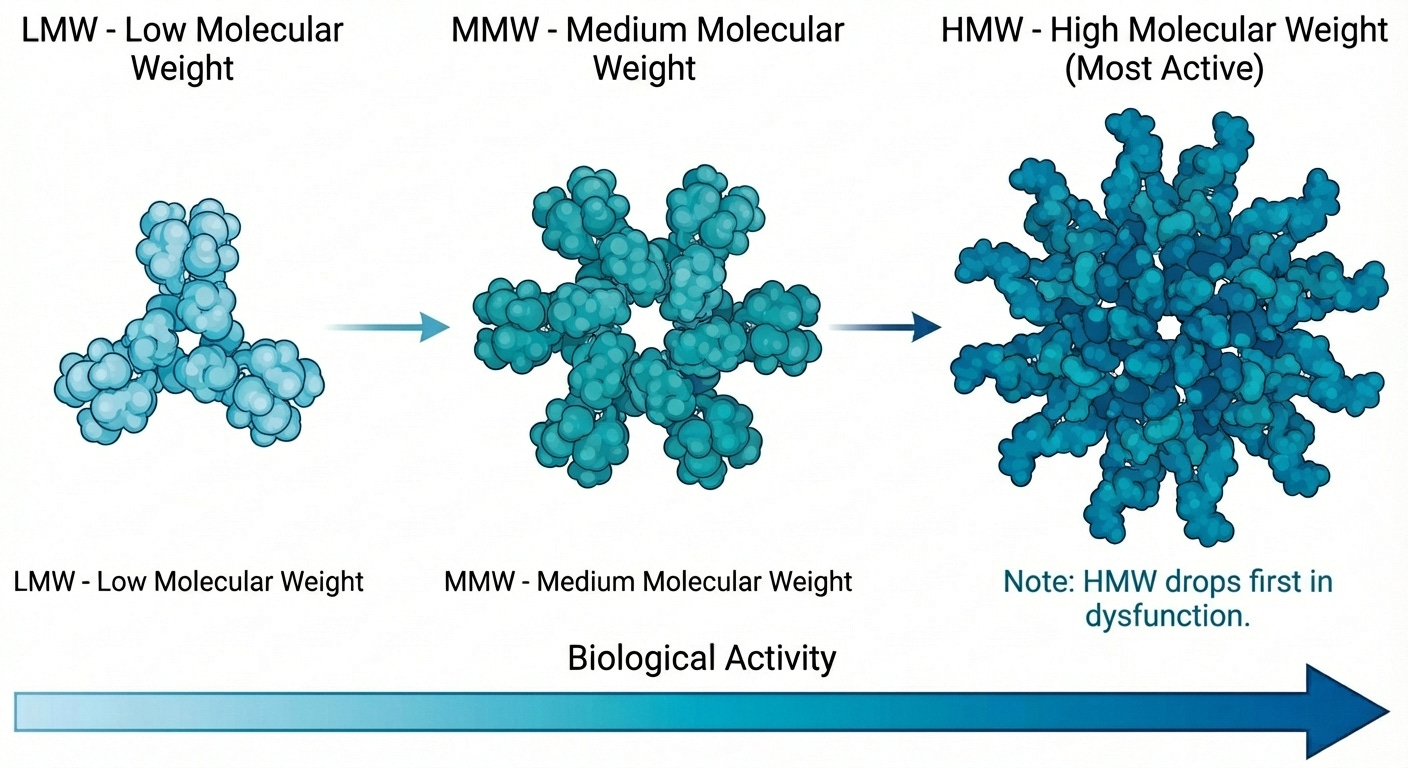

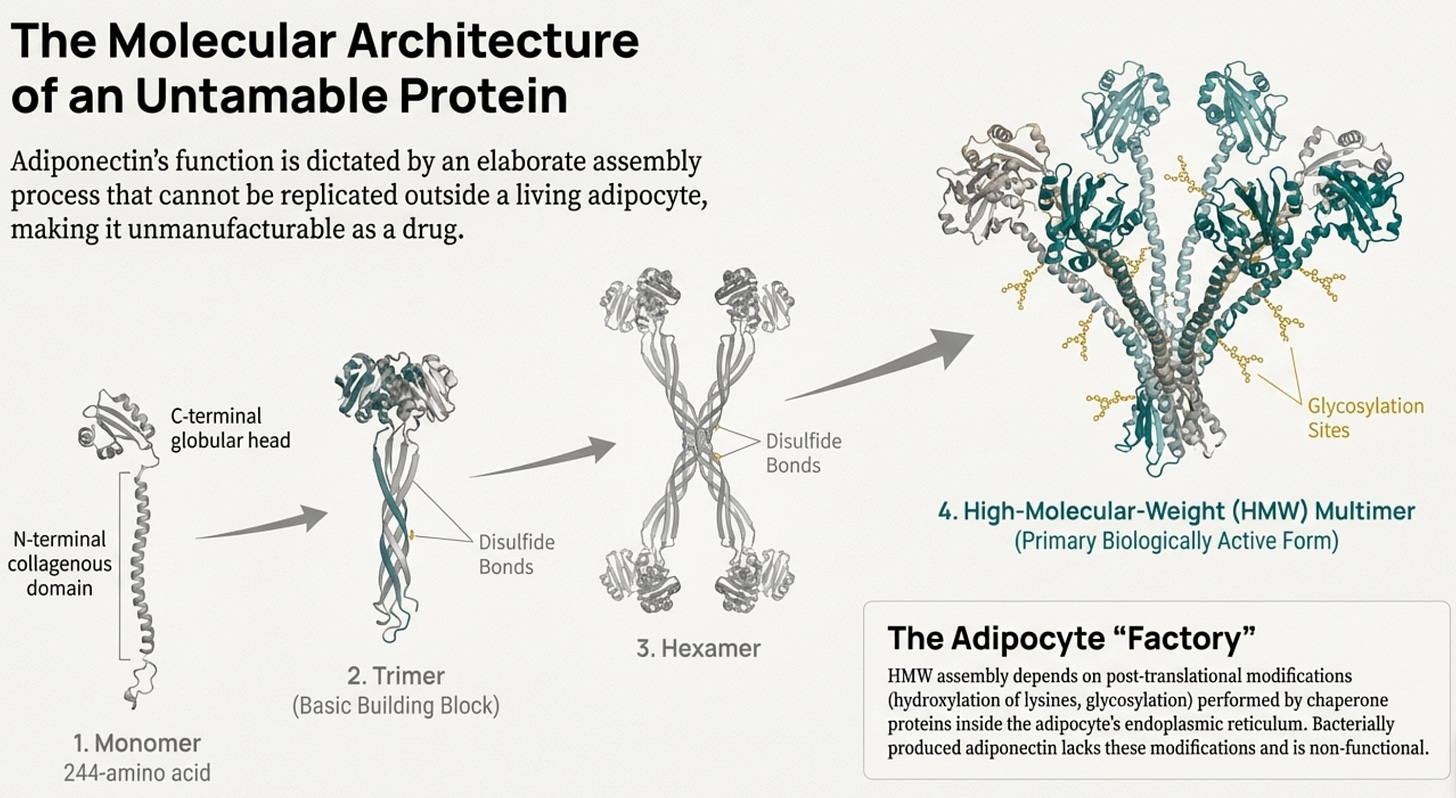

One complexity worth understanding: adiponectin doesn’t circulate as a simple molecule. It assembles into multimeric complexes:

trimers (low molecular weight)

hexamers (medium molecular weight)

large multimers of 12-18 subunits (high molecular weight, or HMW)

The HMW form is the most biologically active. It correlates most strongly with insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular protection. Women have higher HMW concentrations than men, which may partially explain sex differences in metabolic disease timing.

When adipose tissue becomes dysfunctional, HMW adiponectin falls first, the ratio shifts toward less active isoforms before total adiponectin even drops. A “normal” total adiponectin can mask significant early dysfunction if HMW has already cratered. This is the same pattern we see elsewhere and discussed previously: HOMA-IR missing beta cell decline, BMI missing visceral adiposity. The standard measurement hides the signal.

Note to physicians reading this: If you’re going to test (and in metabolically complex patients, you should consider it), HMW adiponectin is ideal. It’s not widely available, but total adiponectin is still informative, especially when it’s low in someone who appears lean or metabolically “normal” by conventional criteria. That discordance itself is diagnostic.

The Reference Range Problem

Here’s where precision medicine meets its limits, and where the research imperative for South Asian populations becomes acute.

Standard adiponectin reference ranges, typically cited as 2-20 μg/mL for total adiponectin, are derived from mixed or predominantly European cohorts. When your doctor orders this test (if they order it at all), the lab report will flag values as “normal” or “abnormal” based on these population norms.

For South Asians, this is worse than useless. It’s actively misleading.

A 2008 Diabetes Care study revealed something that should have rewritten clinical practice: researchers compared insulin-resistant versus insulin-sensitive women in both South Asian and Caucasian groups. In Caucasians, the expected pattern held, where insulin-resistant women had markedly lower adiponectin than insulin-sensitive women. The biomarker tracked the disease.

But in South Asians, there was no significant difference in adiponectin between insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive individuals. A South Asian woman could have profoundly dysfunctional glucose metabolism and still show adiponectin levels indistinguishable from her metabolically healthy counterpart.

The relationship was decoupled.

This finding has been replicated across multiple studies, in Indian teenagers, British South Asians, and migrant populations in Singapore. Adiponectin simply doesn’t correlate as cleanly with insulin resistance, BMI, or cardiometabolic variables in South Asian populations as it does in Europeans. The biomarker relationship that defines the reference ranges doesn’t hold for us.

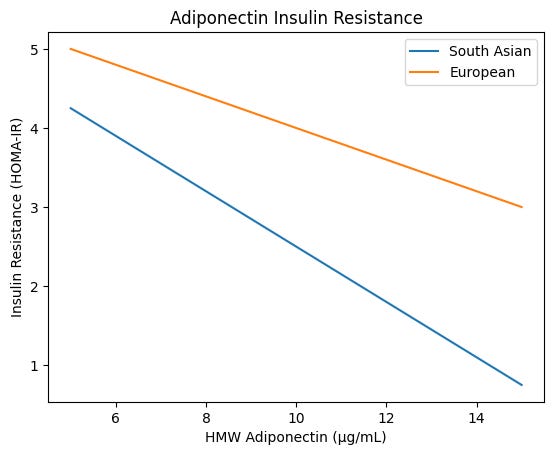

And yet, and this is critical, when adiponectin does drop in South Asians, the consequences are steeper. A 2013 cross-ethnic Canadian study found that ethnicity significantly modified the relationship between HMW adiponectin and HOMA-IR. For every decrease in HMW adiponectin concentration, South Asians showed a greater increase in insulin resistance compared to Europeans. At the same absolute adiponectin level, South Asians had higher HOMA-IR.

The practical implications are disorienting:

A South Asian with “normal” adiponectin by European standards may already be functionally deficient relative to what their physiology requires

The same absolute value means something different depending on ethnicity; 9 μg/mL in a South Asian is not metabolically equivalent to 9 μg/mL in a European

The threshold at which metabolic risk accelerates may be entirely different, and no one has systematically defined it

What’s missing from the literature, and what would constitute a genuine advance in South Asian precision medicine, is foundational work that simply hasn’t been done:

1. Ethnic-specific reference ranges. No major study has systematically derived South Asian-specific optimal ranges or cutoffs for metabolic risk prediction. We’re using a European genotype/phenotype ruler to measure a South Asian body.

2. Population-specific risk thresholds. At what adiponectin level does metabolic risk accelerate in South Asians versus Europeans? The inflection point that should trigger intervention may be entirely different. A South Asian at 7 μg/mL might warrant the same concern as a European at 4 μg/mLl, but we don’t know, because the studies haven’t been powered to answer this.

3. Whether the relationship truly differs or just appears to. Is adiponectin genuinely “decoupled” from insulin sensitivity in South Asians, or are we measuring the wrong form? Perhaps HMW percentage, or a specific multimer ratio, or adiponectin receptor sensitivity matters more in our population. The tools to fractionate and characterize exist, they just haven’t been systematically deployed.

4. Why the difference emerges so early. South Asian infants at 3-6 months , as we talk about below, already show lower adiponectin than European infants despite smaller body size. This isn’t acquired dysfunction, it’s developmental programming. Understanding the genetic and epigenetic drivers could reveal intervention windows that current medicine doesn’t even know to look for.

This gap exemplifies a broader problem. Even sophisticated tools like Function Health panels, full-body MRIs, and continuous glucose monitors interpret their findings against reference populations that don’t include us in representative numbers. You can spend thousands on the most advanced testing available and still receive results calibrated to someone else’s physiology.

The adiponectin test exists. Any commercial lab can run it. But without South Asian-specific interpretation, without knowing what “optimal” means for our population, we’re flying partially blind even when we measure the right thing.

This is a research imperative, not an academic curiosity and something I am genuinely passionate to help further in my role as a physician (stay tuned for something in this regard). One quarter of the global population is South Asian. The diabetes and cardiovascular epidemic unfolding across India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the diaspora is not adequately explained by lifestyle alone. We need our own reference ranges, not because we’re asking for special treatment, but because the current ones are systematically wrong for us. THis remains the most important imperative of our generation.

Until that research exists, clinicians working with South Asian patients should interpret adiponectin results with appropriate skepticism. A “normal” value provides less reassurance than it would in a European patient. A “low-normal” value warrants concern. And the trend over time may matter more than any single measurement, a declining adiponectin in a South Asian patient, even within the “normal” range, should prompt intervention.

Born Different

Here’s where it becomes specific to South Asians.

South Asians have 25-40% lower circulating adiponectin than Caucasians. Not because we’re more obese, this gap persists after adjusting for BMI, total body fat, age, sex, and lifestyle factors.

The SHARE/SHARE-AP study in Canadian populations quantified it: South Asian adiponectin levels of 9.35 μg/mL versus 12.94 μg/mL in Europeans. That’s not a subtle difference.

That gap represents nearly 1.5 standard deviations in most cohorts; not a slight shift, but a fundamentally different physiological baseline.

But here’s what makes this truly concerning: the dose-response relationship is steeper for us.

For each unit decrease in HMW adiponectin, South Asians show greater increases in HOMA-IR than Europeans (p=0.040 for interaction). We get less of the protective signal, and each decrement costs us more in terms of insulin resistance. Even at similar adiponectin levels, the South Asian curve sits at a worse metabolic position, reinforcing the idea of a different physiological baseline, not just a shifted mean.

Less adiponectin. Greater sensitivity to its absence. Double hit.

This is not a lifestyle problem. It is constitutional.

The evidence goes deeper still, to a finding that reframes everything we think about metabolic destiny.

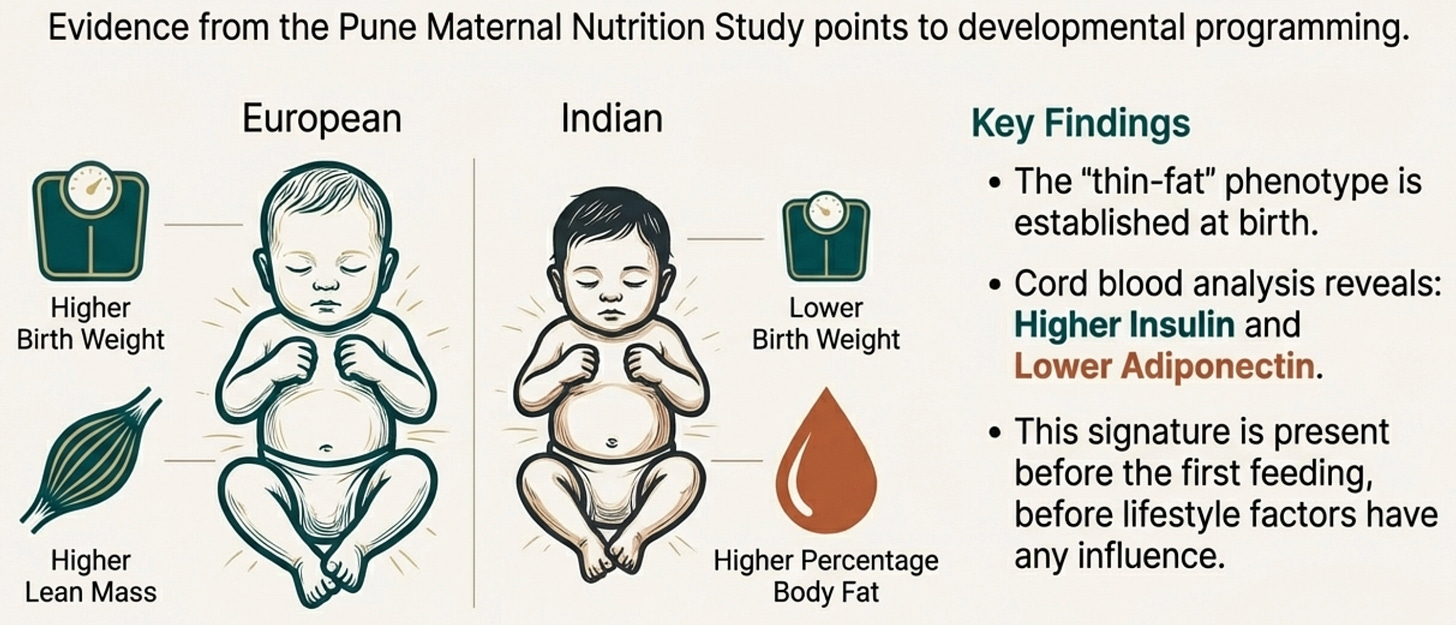

In 2015, the Pune Maternal Nutrition Study documented something remarkable. Indian newborns compared to European newborns showed lower birth weight and lower lean mass, but higher percentage body fat for their size, the thin-fat phenotype already established in utero.

The original Pune data showed preserved truncal fat in lower birth weight babies. More recent body composition studies using precise methods like pea-pod plethysmography in normal birth weight Indian infants haven’t always replicated absolute fat preservation to the same degree. But the core finding persists: higher adiposity relative to lean mass, and lower cord blood adiponectin.

These weren’t premature babies or cases of intrauterine growth restriction. These were full-term, apparently healthy infants already metabolically programmed differently.

And their cord blood? Higher insulin. Lower adiponectin.

Think about what this means. Before a South Asian baby takes its first breath, before the first taste of formula or rice cereal, before the first birthday party (laden with gulab jamun ofcourse!) the metabolic signature is already written. Central adiposity and adiponectin deficiency aren’t things we develop through poor choices. They are part of our developmental architecture.

This pattern has been confirmed in multigenerational Indians in Surinam, in Pakistani children in the UK Born in Bradford cohort, in migrant Indians across Canada and the United States. The thin-fat phenotype travels with us. It is inherited not just genetically but epigenetically, written into how our genes are expressed, passed from mother to child through the intrauterine environment.

When your grandmother tells you that “our family has sugar,” she’s not wrong. She’s just describing the phenotype without the mechanism.

We are born with smaller subcutaneous fat capacity, a tendency toward visceral deposition, and adipocytes that produce less protective signaling from the start.

The Fat That Lies

There’s a reason the uncle with the 32-inch waist had a heart attack. It wasn’t the fat you could see. It was the fat you couldn’t.

The clinical term, as we have discussed previously, is “TOFI”, thin outside, fat inside. Or “metabolically obese, normal weight.” But these sterile phrases don’t capture what’s actually happening: an internal geography of fat distribution that makes standard measurements nearly useless.

Imagine two men, both with a BMI of 24. One is Scandinavian. The other is Gujarati. On paper, they look identical. Under an MRI, they are different species.

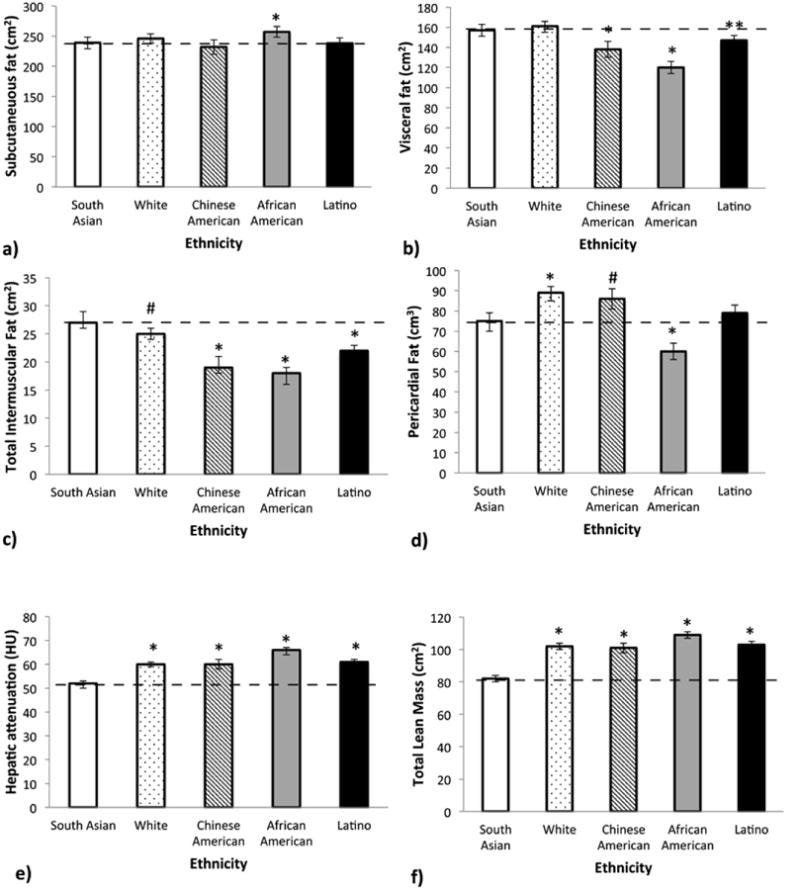

One of my favorite studies, the MASALA study (Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America) compared South Asians to Caucasians, African Americans, Latinos, and East Asians. Even after adjusting for BMI, South Asians had more visceral fat (the deep abdominal fat wrapped around organs), more hepatic fat (fat infiltrating the liver), more intermuscular fat (fat marbled through muscle tissue, like a poorly-graded steak), and less lean muscle mass.

The Gujarati man, at BMI 24, is carrying his fat in the worst possible locations. His subcutaneous fat, the pinchable fat under the skin, may be minimal. But his visceral compartment is stuffed. His liver is fatty. His muscles are infiltrated.

This matters for adiponectin because visceral fat is the primary source of the inflammatory signals that suppress adiponectin production. TNF-α, IL-6, resistin (which MASALA also showed to be higher), these cytokines pour out of visceral adipose tissue, creating a local inflammatory environment that directly inhibits adiponectin synthesis. The more visceral fat you carry, the lower your adiponectin falls.

But the arrow runs both directions. Low adiponectin doesn’t just result from visceral fat accumulation, it promotes further visceral storage. Without adequate adiponectin signaling, insulin resistance worsens, and hyperinsulinemia preferentially drives fat into visceral and ectopic depots rather than metabolically safer subcutaneous sites.

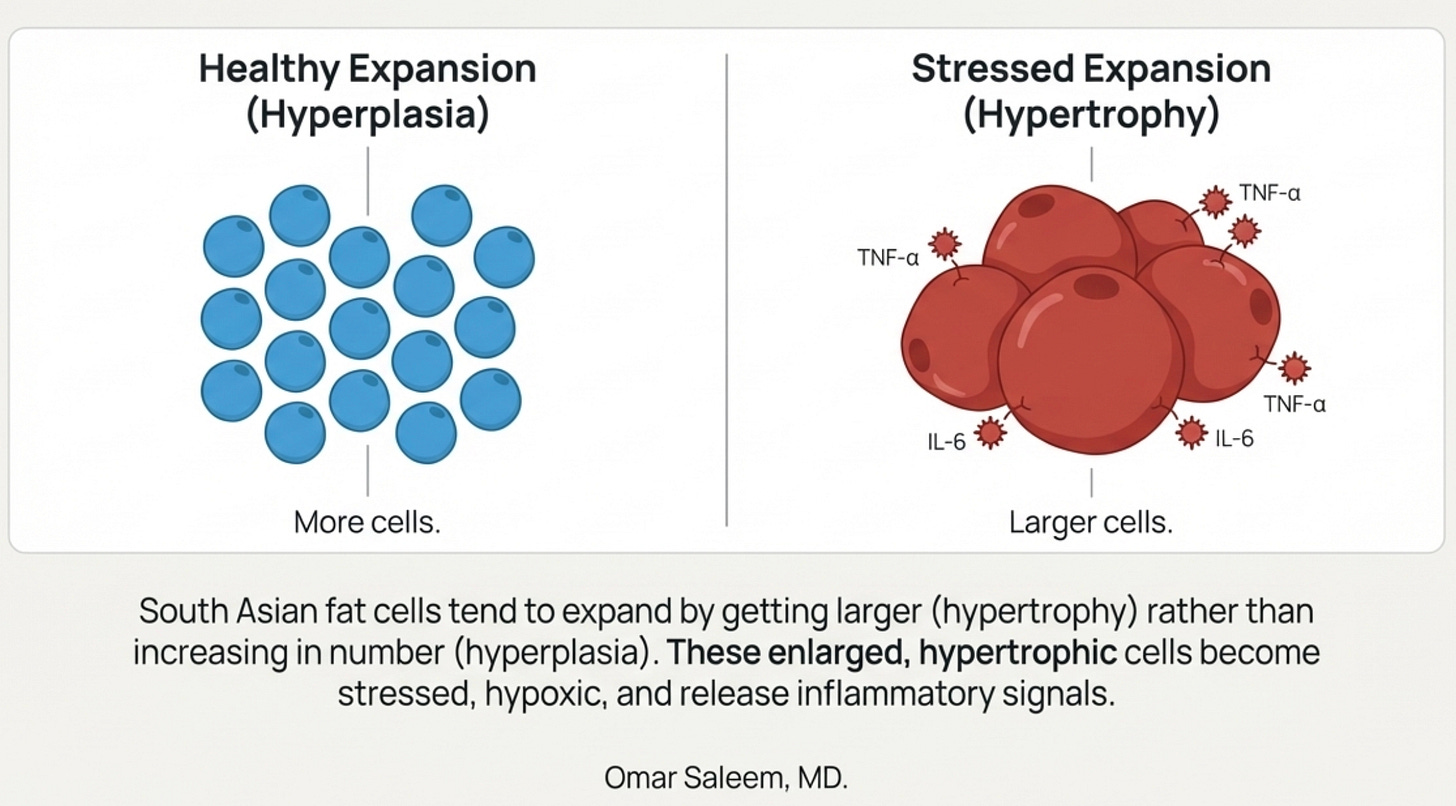

The adipocyte loses its signal to expand healthily; instead, existing cells hypertrophy and new fat spills into the liver, the muscle, the viscera.

This is why the relationship is a vicious cycle rather than a simple cause-and-effect. And for South Asians, both the thin-fat phenotype and constitutively low adiponectin appear to emerge together from the same developmental programming, present from infancy, written into the architecture before lifestyle has any chance to intervene. We don’t acquire visceral fat and then lose adiponectin. We enter the world with both vulnerabilities already in place, each poised to worsen the other.

South Asians enter this cycle at much lower total body weights than other populations.

The MASALA study revealed a striking pattern: South Asians have higher intermuscular fat (fat marbled through muscle tissue) and hepatic fat (fat infiltrating the liver) compared to every other ethnic group studied including Whites, Chinese Americans, African Americans, and Latinos. This held true even after adjusting for BMI. The fat isn’t just in the wrong anatomical compartment; it’s infiltrating the organs themselves.

[Great interview on this below with Dr. Alka Kanaya who led the MASALA study.]

There’s a cellular layer too. South Asian adipocytes are hypertrophic, at the same BMI, our fat cells are physically larger than Caucasian fat cells. This isn’t just a curiosity. Hypertrophic fat cells are stressed fat cells. They outgrow their blood supply and become hypoxic. They trigger the unfolded protein response, a cellular stress alarm. They cannot produce adequate adiponectin because they are too busy trying not to die.

The thin-fat phenotype isn’t about being thin. It’s about carrying a normal amount of fat in catastrophically distributed ways, in cells that are already exhausted.

Here’s where it gets dark: the adipocyte itself has mitochondria. When those mitochondria fail, overwhelmed by lipid influx, hypoxic from adipocyte hypertrophy, damaged by ROS, the adipocyte’s ability to produce adiponectin declines further.

Less adiponectin → less mitochondrial biogenesis → more mitochondrial dysfunction → less adiponectin.

The fat cell is both the source of the problem and a victim of it. (More on that below).

The Genetic Inheritance

The story deepens at the level of DNA.

The ADIPOQ gene, located on chromosome 3q27, encodes the adiponectin protein. Variations in this gene, what we call single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, help explain why adiponectin levels vary so dramatically between individuals and populations.

Several SNPs are significantly more common in South Asian populations:

rs1501299 (+276 G/T): In the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study, the TT genotype conferred 1.65-fold higher obesity risk. This variant sits in an intron, affecting how the gene is regulated rather than the protein itself.

rs822396 (-3971 A/G): In North Indian populations, the GG genotype associates with 3.6-fold higher Type 2 Diabetes risk. That’s not a modest increase, it’s the difference between a 10% and a 36% lifetime probability.

rs2241766 (+45 T/G): The G allele is more common in diabetic versus non-diabetic Punjabis (29% vs 21.5%, OR 1.49), and this same variant is associated with coronary artery disease susceptibility specifically in South Asian and European populations—but not in East Asians.

Broader meta-analyses show these SNPs have variable effects across ethnicities, sometimes protective in Caucasians, risk-conferring in South Asians. This variability is precisely the point: population-agnostic guidelines derived from European cohorts systematically miss genetic risks that behave differently in our background.

What’s critical to understand: these variants aren’t destiny. They’re conditional. In a traditional rural setting with high physical activity, lower glycemic load, and energy scarcity, these SNPs may remain silent; the environment never pulls the trigger. But in a sedentary urban context with refined carbohydrates and chronic caloric surplus, the same genotype becomes a landmine. That 3.6-fold diabetes risk from rs822396 GG isn’t inevitable; it’s what happens when the modern environment unmasks a genetic vulnerability that was neutral for millennia.

This reframing matters because it returns agency to the equation. You can partially recreate the “masking” environment through lifestyle, not perfectly, but meaningfully.

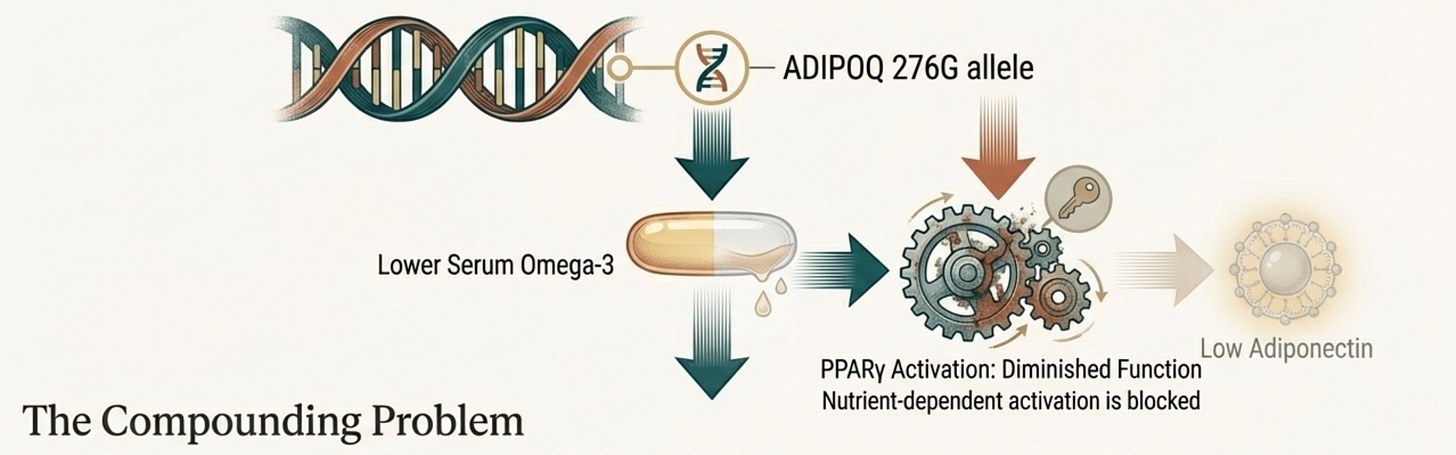

Perhaps most fascinating is a gene-nutrient interaction involving the ADIPOQ 276G allele. South Asian carriers of this variant show reduced omega-3 fatty acid levels in their serum. Omega-3s are natural ligands for PPAR-γ, the nuclear receptor that drives adiponectin transcription.

So this variant creates a double bind: a gene that produces less adiponectin, housed in a body that retains fewer of the nutrients needed to stimulate that gene.

This has direct clinical implications. Omega-3 supplementation for South Asians carrying this variant isn’t generic “heart health” it’s targeted correction of a specific gene-nutrient mismatch.

When your family seems to “run diabetic” or “have heart problems,” this is part of what you’re inheriting. Not fate, exactly, but a set of biological constraints that require specific countermeasures.

The Energetic Frame: When the Mitochondria Struggle

There’s one more layer to this story, and it’s the one that ties everything together.

In our practice, we have recently been integrating to view metabolic dysfunction through the lens of what we call Energy Resistance; the idea that biological systems must resist electron flow to do useful work, but excess resistance creates friction, heat, and damage.

Think of your mitochondria as power plants. Electrons flow from the food you eat down a series of protein complexes, and that flow drives the production of ATP, cellular energy. Some resistance in this system is necessary; it’s what allows the energy to be captured rather than dissipated. But too much resistance means the electrons back up, leak out, and form reactive oxygen species, molecular shrapnel that damages proteins, membranes, and DNA.

South Asians show signs of high intrinsic energy resistance. Our VO2max (maximal oxygen uptake) is lower. Our skeletal muscle oxidative capacity is reduced. We have fewer mitochondria per muscle cell, and the ones we have may be running tightly coupled, efficient in the Prius sense, hitting capacity quickly rather than having headroom to spare.

Adiponectin, in this framework, functions as a conductance signal. When adiponectin binds its receptors and activates AMPK, it’s essentially telling the system: open the gates, let the electrons flow, build more mitochondria, burn the fuel. It lowers resistance. It enables efficient energy production. Through the AMPK-PGC-1α axis, it drives mitochondrial biogenesis, the creation of new mitochondria to handle the load.

The chronic hypoadiponectinemia of South Asians means we’re running our metabolic machinery with the brakes partially engaged. The electrons back up. The reactive oxygen species accumulate. The inflammation rises. And the very fat cells that should be producing adiponectin become too stressed to make it.

Here’s where it gets dark: the adipocyte itself has mitochondria. When those mitochondria fail, overwhelmed by lipid influx, hypoxic from adipocyte hypertrophy, damaged by ROS, the adipocyte’s ability to produce adiponectin declines further.

Less adiponectin → less mitochondrial biogenesis → more mitochondrial dysfunction → less adiponectin.

The fat cell is both the source of the problem and a victim of it.

You feel this as afternoon fatigue despite adequate sleep. As the heaviness after a meal that seems out of proportion to what you ate. As the difficulty building muscle despite consistent training. As the sense that your body is working harder than it should to do basic things.

This isn’t weakness or laziness. It’s bioenergetic constraint. And it requires specific interventions.

Bringing It Together

If you’ve been following this newsletter, certain patterns should be emerging.

We’ve talked about beta cells that have lower reserve and burn out faster—the fragile engine that redlines under chronic demand. About ghrelin that’s suppressed when it should be pulsatile, removing a brake on insulin secretion and a growth hormone stimulus that should be protecting lean mass. About mitochondria that are efficient but hit capacity quickly, backing up electrons and triggering resistance. About subcutaneous fat that overflows early into visceral depots because the tank is smaller to begin with.

Adiponectin touches all of these.

It protects beta cells directly and reduces the hepatic glucose load that exhausts them. It participates in reciprocal regulation with ghrelin through the gut-adipose axis. It drives mitochondrial biogenesis that would relieve the electron backup. It determines whether adipocytes expand healthily or hypertrophy and overflow.

When adiponectin is adequate, it buffers against all of these failure modes. When it’s constitutively low, as it is in South Asians from birth, every system becomes more vulnerable.

The adipocyte isn’t just another organ in the story. It’s increasingly looking like the upstream node; the source from which many downstream problems flow.

This is why I’m working on a deeper exploration of adipose tissue itself for an upcoming post. The biology of adipocyte expandability. Hyperplasia versus hypertrophy. The “adipose tissue overflow hypothesis.” What it means to have fat tissue that fails at lower thresholds than other populations.

Adiponectin is our window into that adipocyte. When it’s low, it tells us the fat cell is struggling. The question becomes: can we intervene at the source?

The part that follows is primarily how we tackle and how we can improve both adiponectin and, just as importantly, the pathways that adiponectin impacts, especially AMP kinase. To be honest, it is extremely dense in scientific and clinical detail as I myself could not find any good collection of information, so I ended up putting together what we know so far on my own. I have tried to break it down in a way that I would think of this as a physician and starting from the history of adiponectin guided therapy that we have evidence of and then going into possible options that we could use to treat it. This is by no means any kind of medical advice or clinical advice or medications or supplements to take and I think this can become a good base to work off of on how we approach treatment. It is also a much more complicated section which is why I tried to bring everything together in the previous paragraphs. I would also love your feedback on if this is something that you’d like me to do more of. Maybe we can start chat threads on Substack Chat to discuss it further.

What Actually Works

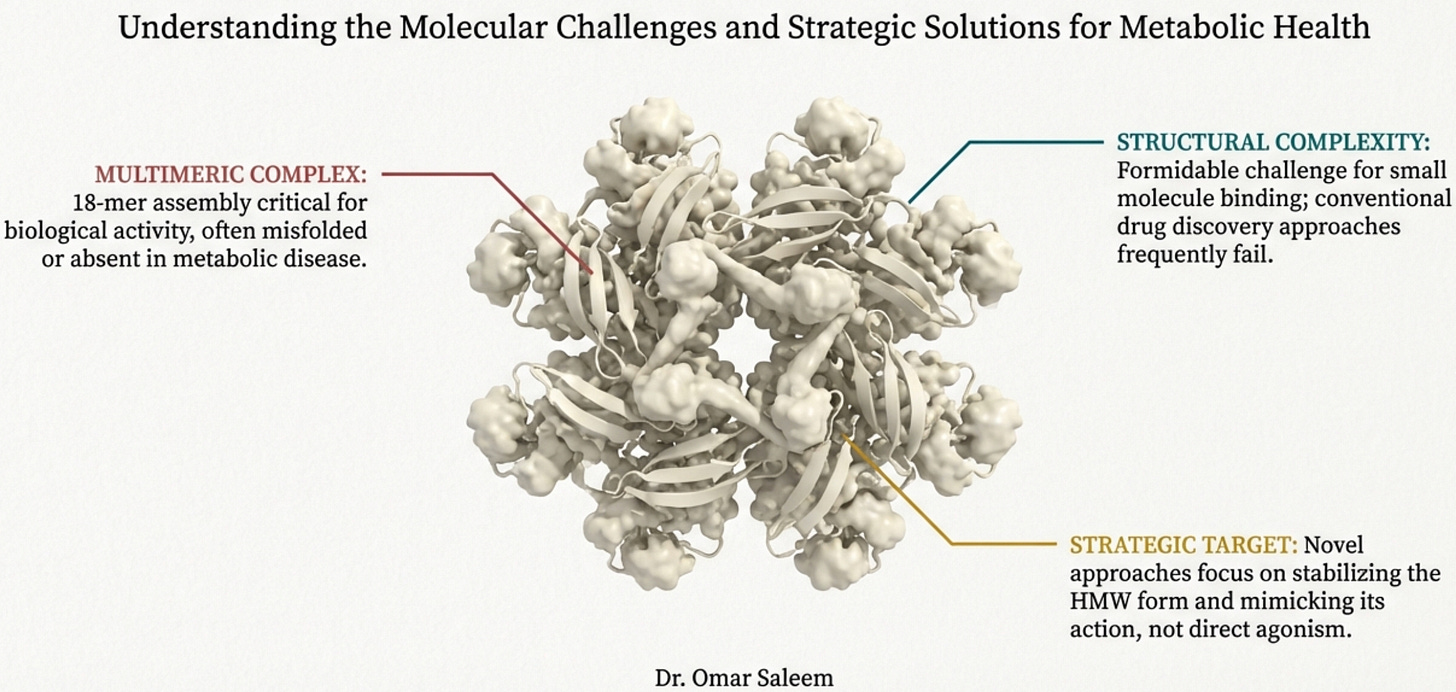

Here’s the uncomfortable truth that explains why adiponectin optimization has remained on the margins of clinical medicine: we can’t give adiponectin directly. The protein is undruggable, the receptor agonists haven’t made it to metabolic trials, and there’s no pill that simply raises levels. The pharmaceutical industry has largely moved on.

This isn’t for lack of trying. Understanding why the direct approaches failed is essential context for the workarounds we’re forced to use.

Why You Can’t Just Give Adiponectin

At first glance, the solution seems obvious: adiponectin is low, so give adiponectin. We do it with insulin, with growth hormone, with EPO. Why not adiponectin?

The answer lies in the molecule’s baroque complexity. Adiponectin isn’t a simple hormone like insulin. It’s a 244-amino acid protein that must assemble into elaborate multimeric structures to function. The basic building block is a trimer, three adiponectin molecules wound together. These trimers then combine into hexamers. And the hexamers further aggregate into high-molecular-weight (HMW) multimers containing twelve to eighteen individual protein chains massive molecular machines that dwarf most circulating hormones.

Here’s the problem: only the HMW form appears to be the biologically active species for insulin sensitization. The trimers and hexamers circulate but don’t produce the metabolic effects we want. And getting a protein to properly assemble into HMW multimers requires specific post-translational modifications, disulfide bonds at the right cysteines, hydroxylation of conserved lysines, glycosylation of those hydroxylysines. These modifications happen in the endoplasmic reticulum of living adipocytes through the action of specific chaperone proteins. You can’t replicate this in a bacterial expression system. Bacterially produced adiponectin lacks these modifications entirely and fails to form proper trimers, let alone the HMW multimers that actually work. Let’s bring back the original diagram:

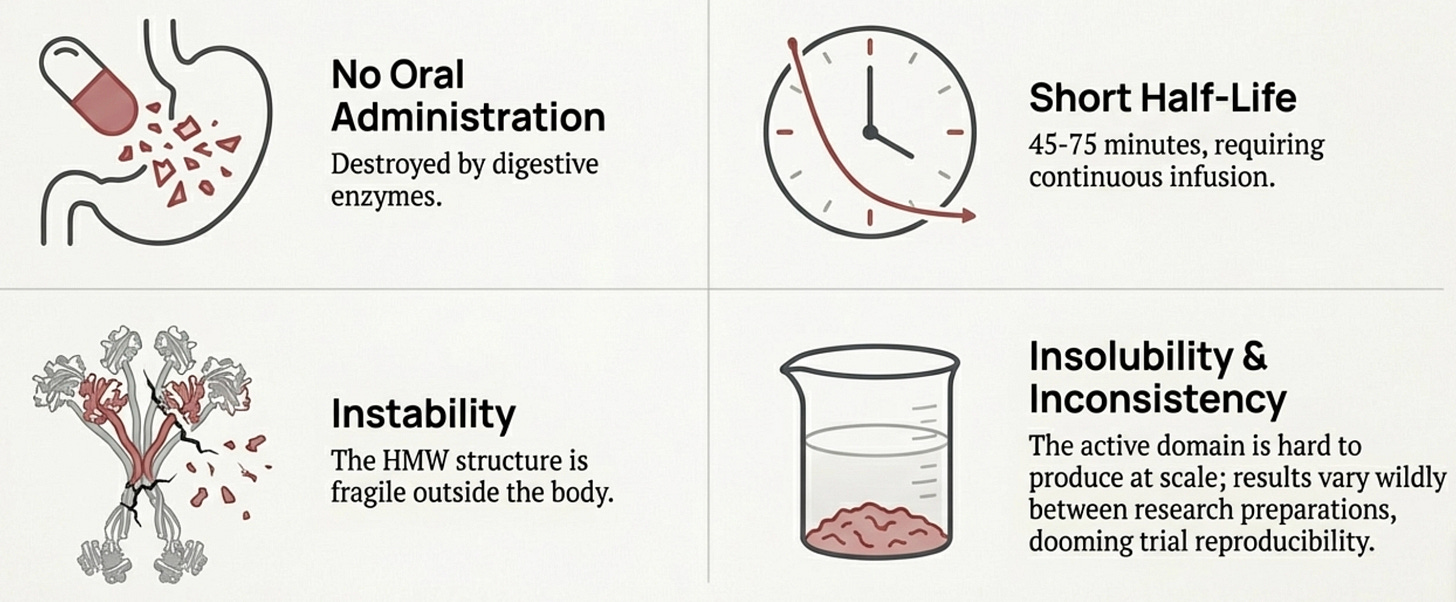

Even if you could produce properly multimerized adiponectin, you’d face brutal pharmacokinetics. The protein has a half-life of 45-75 minutes—meaning you’d need continuous infusion or frequent injections. It can’t be given orally because digestive enzymes destroy it. The HMW multimers are unstable outside the body, requiring stringent storage conditions that don’t translate well to clinical use. And the C-terminal globular domain—where the active site lives—is notoriously insoluble, complicating large-scale production.

The diverse molecular forms create reproducibility problems that would doom any clinical trial. In vitro and in vivo results vary wildly depending on which adiponectin preparation you use—full-length versus globular, bacterial versus mammalian expression, fresh versus stored. No pharmaceutical company can build a drug development program on such inconsistent biology.

a bit of history before we understand what needs to be done.

The AdipoRon Story

If you can’t give the protein, why not make a small molecule that mimics it? This was the thinking behind AdipoRon, discovered in 2013 at the University of Tokyo through screening a chemical library for compounds that activated AMPK in muscle cells. It was the first orally available adiponectin receptor agonist—a drug you could swallow that would theoretically replicate what adiponectin does.

The animal data looked spectacular. AdipoRon, given orally at 50 mg/kg to genetically obese diabetic mice, reduced plasma glucose levels comparably to adiponectin protein injection. After two weeks, the mice showed markedly improved glucose tolerance, reduced insulin resistance, and better lipid profiles. When put on a high-fat diet, AdipoRon-treated mice lived longer than untreated controls. It appeared to work through both AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, activating the AMPK-PGC1α and PPARα pathways that adiponectin normally engages. The papers proliferated: AdipoRon for diabetes, for fatty liver, for cardiovascular disease, for neurodegeneration, for cancer.

Yet over a decade later, AdipoRon has never entered human clinical trials for metabolic disease.

The reasons are instructive. The binding affinity of AdipoRon to its receptors is relatively weak, dissociation constants of 1.8 and 3.1 micromolar for AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 respectively. In pharmaceutical development terms, this is poor. The concentration needed to activate AMPK in cells (EC50 around 10 micromolar) falls below the threshold that typically justifies advancing a compound through development. Current pharmaceutical go-no-go criteria, as one review put it, “are not in favor of pursuing a candidate with such a low cellular activity.”

There’s also the problem of systemic toxicity testing. Small molecules that activate receptors throughout the body face stricter safety hurdles than topical preparations. This difficulty is evident even in the well-established GLP-1 class, the most famous single receptor activators, where developing oral small molecules has faced far greater toxicity scrutiny than their peptide predecessors.

The one adiponectin mimetic that has reached human trials, a peptide called ADP355, is being tested only as eye drops for dry eye disease, where systemic exposure is minimal. For metabolic indications requiring whole-body effects, no adiponectin receptor agonist has yet convinced regulators or pharmaceutical companies that the benefit-risk profile justifies human testing.

The adiponectin paradox adds complexity: in certain chronic conditions (heart failure, chronic kidney disease, established coronary disease), higher adiponectin levels correlate with worse outcomes.

This may represent compensation, the body upregulating a protective hormone in the face of overwhelming disease, but it gives pharmaceutical companies pause. A drug that raises adiponectin signaling might help early-stage metabolic dysfunction while harming patients with established cardiovascular disease. The heterogeneous responses across disease stages make clinical development treacherous.

The Implication

This history matters because it explains why we’re forced into indirect approaches. The pharmaceutical industry hasn’t ignored adiponectin out of disinterest, billions of dollars were spent chasing it. The biology proved intractable. The protein is too complex to manufacture, the receptor agonists too weak to develop, the clinical variability too dangerous to navigate.

So how do we think about intervention?

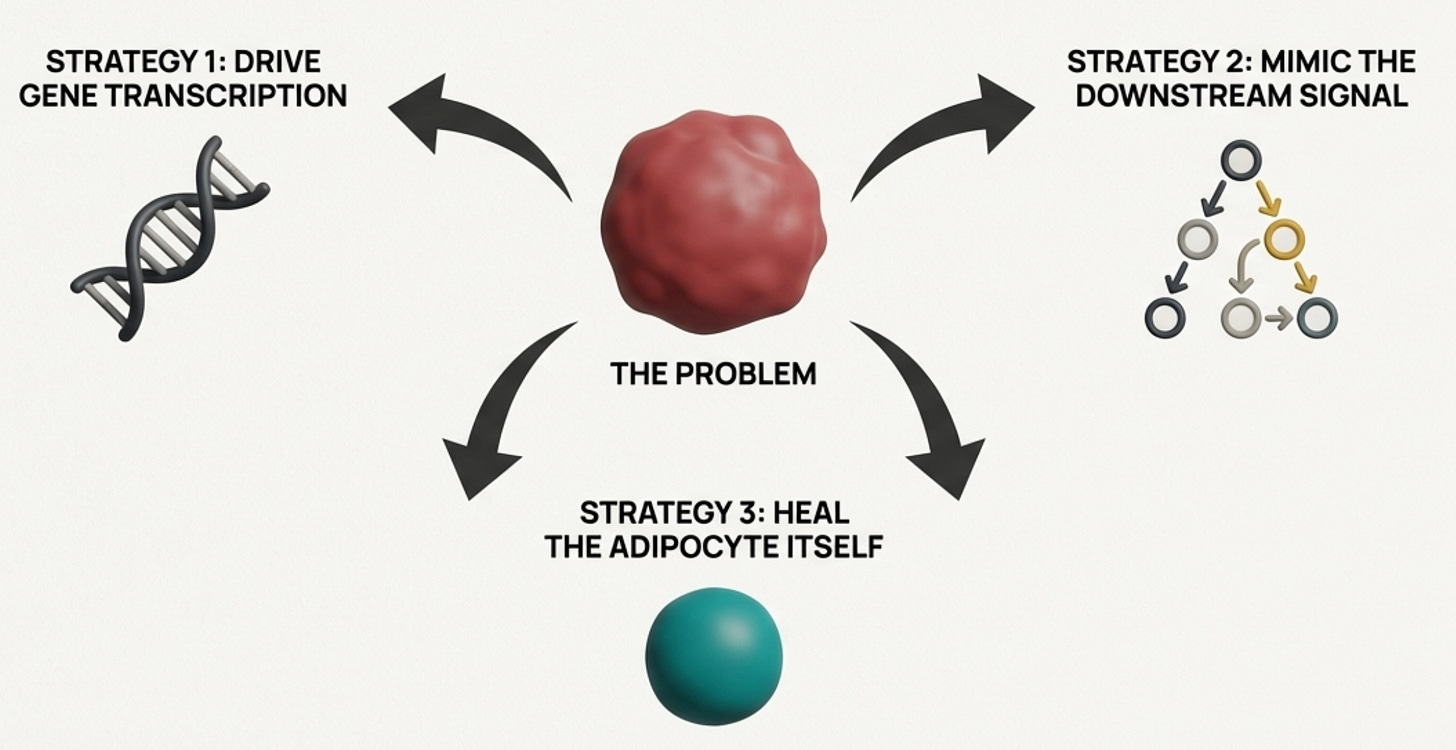

We have three strategic options: increase production at the source by making the adipocyte produce more adiponectin; mimic the downstream signal by activating the pathways adiponectin would have activated; or fix the adipocyte itself, addressing the cellular dysfunction that’s suppressing production in the first place. Each approach has different tools and different implications. The most effective protocols combine all three.

Strategy 1: Drive Adiponectin Gene Transcription

Adiponectin production is controlled primarily by PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), the master transcription factor of adipocyte differentiation and function. If you activate PPARγ, you turn up the adiponectin gene.

This is why thiazolidinediones produce the largest adiponectin increases of any intervention, two to threefold. Pioglitazone is a direct PPARγ agonist. It’s literally pressing the “make more adiponectin” button at the genetic level. The trade-offs (fluid retention, bone density concerns, weight gain) mean they’re not first-line for everyone. You’re activating a powerful switch with broad downstream effects. But for severe, refractory cases with dangerous metabolic trajectories, they remain a tool worth considering.

For most patients, we look for gentler PPARγ modulators. Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) are PPARγ agonists that activate the receptor enough to drive adiponectin translation without the full adipogenic program. This is why therapeutic-dose omega-3s have metabolic effects beyond “heart healthy fats.” They’re actually modulating nuclear receptor signaling in the adipocyte.

The gene-nutrient interaction we discussed earlier makes this especially relevant: ADIPOQ variants that reduce adiponectin production are also associated with lower omega-3 levels. Correcting the nutrient deficit removes a brake on a gene that’s already underperforming.

Curcumin (a derivative of haldi (turmeric)) (in bioavailability-enhanced forms as the key is absorption) also acts as a PPARγ modulator, with the added benefit of NF-κB suppression, addressing both the transcriptional drive and the inflammatory suppression of adiponectin simultaneously. There’s a certain symmetry in finding that a compound central to South Asian cuisine has therapeutic relevance for our specific metabolic vulnerabilities.

Strategy 2: Bypass Adiponectin and Activate Its Downstream Pathways

If we can’t raise adiponectin adequately, we can ask: what would adiponectin have done? And can we achieve that effect through another route?

Adiponectin’s major downstream effector is AMPK, the master switch for cellular energy metabolism. Anything that activates AMPK independently is essentially doing adiponectin’s job for it.

High-intensity interval training is the most potent physiological AMPK activator we have. The energy depletion during intense intervals triggers AMPK directly in muscle tissue; increased glucose uptake, fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial biogenesis. HIIT produces larger metabolic benefits than moderate continuous exercise not because it burns more calories, but because it creates the demand signal that low adiponectin fails to provide.

This reframes exercise prescription for the South Asian patient. It’s not about “burning off” dietary excess. It’s about pharmacologically activating a pathway that your adipose tissue isn’t adequately stimulating. The intensity matters more than the duration. A 45-minute moderate treadmill walk is not metabolically equivalent to 20 minutes of intervals with genuine high-intensity efforts.

Disclaimer Reminder: Please consult a trainer or your physician prior to trying these, this is just for education purposes.

Berberine activates AMPK through inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, a different mechanism than adiponectin, but converging on the same master switch. It also appears to specifically promote HMW adiponectin assembly, giving you both the bypass and the source correction. Some trials show efficacy comparable to metformin for glucose control.

Metformin itself works partly through AMPK activation (though its mechanisms are multiple and debated). This may explain why it remains useful in South Asian populations even when it doesn’t address beta cell protection, it’s compensating for the downstream signal that low adiponectin should have provided.

Strategy 3: Fix the Adipocyte Itself

This is the most upstream approach and potentially the most powerful.

Remember: adiponectin falls because the adipocyte is sick. Hypertrophic, hypoxic, inflamed, mitochondrially dysfunctional. If we can restore adipocyte health, adiponectin production should improve as a consequence.

GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide, tirzepatide, soon retatrutide) work here at multiple levels. They reduce caloric intake, yes, but more importantly they preferentially mobilize visceral fat and reduce adipocyte size. Smaller adipocytes are healthier adipocytes; better oxygenated, less inflamed, more functional. The 16-23% adiponectin increases seen with GLP-1 agonists aren’t the primary mechanism; they’re a readout that the adipocyte is recovering.

Recent meta-analyses show greater cardiovascular protection in Asian populations than in White populations (hazard ratio 0.69 vs 0.85), probably because these drugs target the specific adipocyte pathology we carry. If you’ve been told you’re “not heavy enough” for these medications, push back. The weight thresholds were developed for European populations.

SGLT2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) increase adiponectin through mechanisms we don’t fully understand; possibly by shifting substrate utilization in ways that reduce adipocyte stress, possibly through effects on visceral fat depots. The fact that the mechanism is unclear doesn’t diminish the clinical relevance: these agents improve adipokine profiles while providing cardio-renal protection, which matters given our accelerated trajectory toward those complications.

Resistance training deserves special mention here. By building skeletal muscle, you’re creating a larger glucose sink, more tissue that can clear glucose from circulation, reducing the demand on insulin secretion, reducing the hyperinsulinemia that itself suppresses adiponectin. South Asians have lower lean mass at every BMI, so muscle isn’t cosmetic, it’s metabolically therapeutic.

Weight loss itself, specifically, fat mass reduction that preserves lean mass, shrinks adipocytes back toward functional size. But the type of weight loss matters enormously. Crash dieting that loses muscle while preserving visceral fat doesn’t fix the adipocyte problem and may worsen it. This is why we emphasize protein-forward nutrition and resistance training during any weight loss intervention.

Synthesizing a Multi-Target Intervention

What emerges from this framework is that no single intervention is sufficient. The patient with constitutively low adiponectin, the typical South Asian metabolic phenotype, needs a strategy that hits multiple nodes: PPARγ activation to drive transcription, direct AMPK activation to bypass the missing signal, adipocyte rehabilitation to fix the source, and glucose sink expansion to reduce downstream burden.

The pharmacologic agents, GLP-1 agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, potentially low-dose pioglitazone in refractory cases, layer onto this foundation. They’re not substitutes for the lifestyle architecture; they’re amplifiers of it.

This framework also opens the door to thinking about novel approaches. Anything that improves adipocyte mitochondrial function should theoretically help, which brings us to photobiomodulation with near-infrared light (810-850nm), which stimulates mitochondrial Complex IV. But here’s the nuance most discussions miss: melanin absorbs red light. If you have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, V, or VI, common across South Asian populations, visible red light (630-660nm) will be significantly absorbed by your epidermis before reaching deeper tissues.

You need near-infrared wavelengths specifically, which penetrate past the melanin barrier. The one-size-fits-all protocols developed for lighter-skinned populations will underdeliver for us.

[Working on building a tool to help with this which should be available end of the year (hopefully).]

Cold exposure, which activates brown adipose tissue and may influence white adipocyte function, deserves investigation in this population. Time-restricted eating, compressing the eating window to 8-10 hours, with most calories consumed earlier in the day, may better align nutrient intake with adiponectin’s natural circadian rhythm, which typically peaks in late morning.

The framework gives you a map. The specific interventions are waypoints on that map, not the territory itself.

The Practical Approach

If you’ve read this far, firstly thank you for reading. You now have deeply understand something most South Asians never learn: that the metabolic vulnerability you’ve observed in your family, felt in your own body, and worried about for your children has a mechanistic basis. It’s not destiny. It’s biology, and biology can be addressed. We remain optimistic as always at changing this trajectory.

Recalibrate your thresholds. A BMI of 24 is not “fine” for a South Asian. Neither is a 34-inch waist in a man or a 32-inch waist in a woman. The evidence supports action at BMI ≥23 and waist circumference ≥90cm (men) / ≥80cm (women). If your doctor uses standard cutoffs, educate them, or find a doctor who understands ethnicity-specific risk.

Request the right tests. Standard lipid panels miss qualitative defects common in South Asians (small dense LDL, dysfunctional HDL). Ask for apolipoprotein B, which captures atherogenic particle number. Ask for fasting insulin and calculate HOMA-IR; you may be insulin resistant with normal fasting glucose. HMW adiponectin is ideal but not widely available; total adiponectin is still informative, especially when it’s low in someone who appears lean or metabolically “normal.” That discordance tells you something is wrong at the adipocyte level, even if standard markers haven’t caught up yet.

Target visceral fat, not just weight. The number on the scale matters less than where the fat sits. Interventions that specifically reduce visceral adiposity, GLP-1 agonists, HIIT, Mediterranean diet, deliver more metabolic benefit than the same weight loss achieved through muscle wasting or extreme caloric restriction.

Think mitochondrially, cannot stress this enough. And unfortunately most clinical approaches near completely ignore the mitochondria. If you experience fatigue, poor exercise tolerance, or a sense that your body doesn’t produce energy efficiently, build muscle as expected, you may be encountering the energy resistance that underlies our phenotype. Interventions supporting mitochondrial function, CoQ10, NAD+ precursors, regular high-intensity exercise, adequate sleep, morning light exposure, address the upstream problem.

Advocate for yourself. The clinical guidelines, the BMI charts, the risk calculators—they were built on European cohorts. They systematically underestimate your risk. You are not being hypochondriac when you push for earlier intervention. The data supports you.

Optimism is Paramount

There’s a particular grief in watching your family members fall, one by one, to diseases that were “managed” but never prevented. In hearing “your numbers look good” while sensing that something is wrong. In knowing that the medical system sees you but does not see the specific body you inhabit.

Adiponectin is not the whole story. But it is a crucial chapter, a molecular key that unlocks understanding of why South Asian bodies fail in the particular ways they do. The thin-fat phenotype, the visceral fat accumulation, the insulin resistance at normal weight, the cardiac events that arrive decades too early, adiponectin deficiency runs through all of it.

And if you’ve been following along, you can see how the threads connect: the beta cell under chronic demand, the ghrelin signal gone quiet, the mitochondria running at capacity, the subcutaneous tank that overflows early. Adiponectin sits at the center, the letter that should be keeping all these systems in communication.

In our practice, we’re building a precision medicine protocol that takes these differences seriously. Not as an afterthought or a footnote, but as the foundation. Because until medicine learns to see our specific biology, we have to see it for ourselves.

The metabolic dice may be loaded. But understanding how they’re loaded is the first step toward changing the odds.

Optimism is paramount.

-omar

edited with Claude; Deep research for using Gemini, Manus and Claude

Disclaimer: This post is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult your physician before making changes to medications or supplements.